CURIO

Curio traces collections at Harvard

Towers

Diplomas

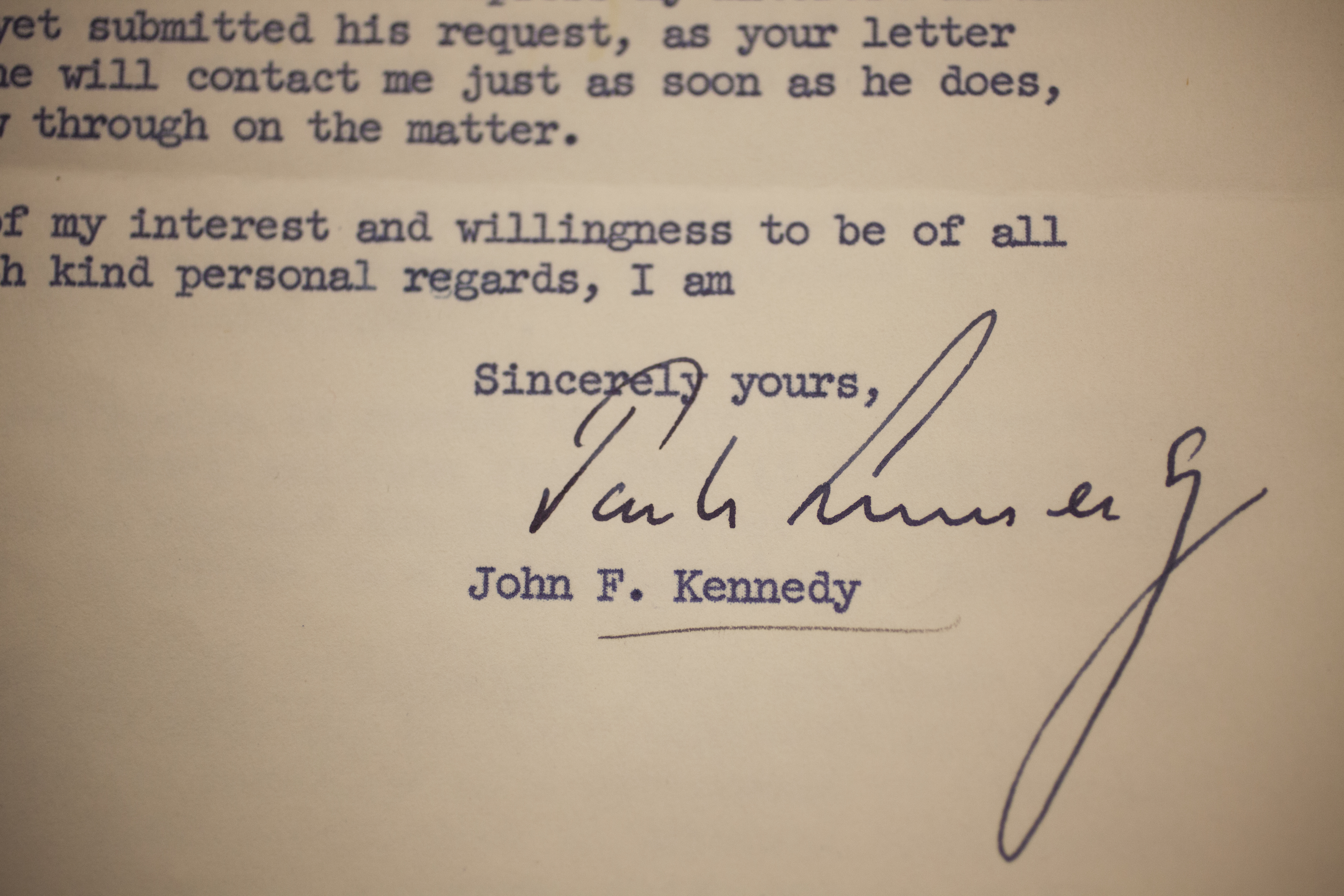

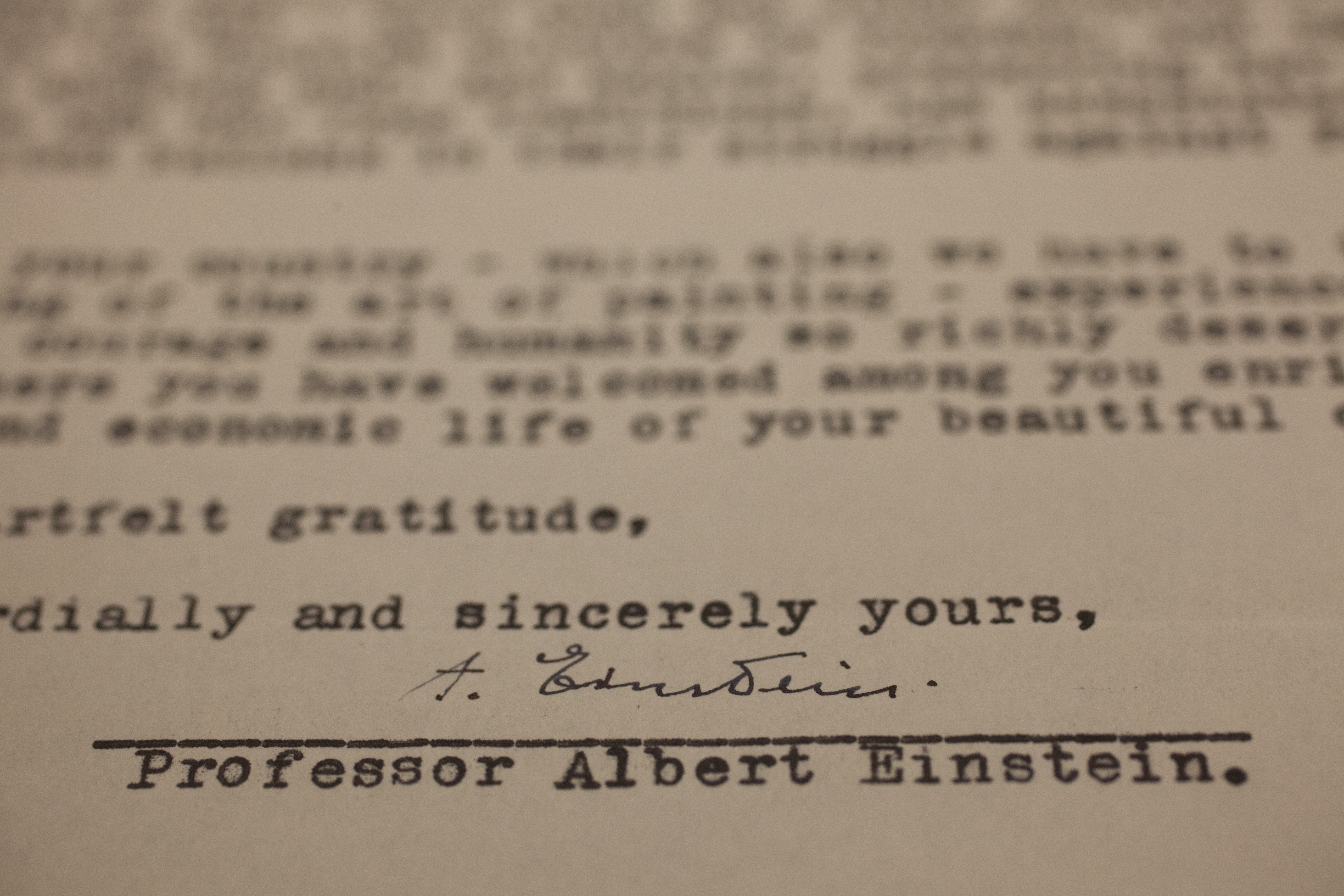

Signatures

Hats

Leaves

Political buttons

Outdoor sculptures

Miniature stage sets

Walter Gropius’ bowties

Veritas shields

No collection is too large or too small.

Taking talking leaves

Harvard curios that are fleeting and ephemeral and free

by Corydon Ireland

After nearly four centuries, Harvard has attics full of curios and treasures. Among them are the whimsical, the earnest, and the odd: Emily Dickinson’s writing desk, Houdini’s handcuffs, a T.S. Eliot bowler, and drawers of fish, bone, and botany specimens that date back to the 18th century.

Then there are those Harvard curios that are fleeting and ephemeral and free: principally the fallen leaves that every autumn tourists and passers-by tuck into pockets and bags as mementos of a place, Harvard Yard, that shimmers with meaning and history. This pastime proves again that — despite a veneer of civilization — humankind holds in its core a sense of magic in the leaves, sticks, shells, and stones of the outside world: that such totems will give us power, will make memory linger, and will link us to gods of nature long forgotten.

Last week, a tourist paused to pick up a large leaf of gold and green that had fallen from a Harvard Yard sugar maple tree. She had other choices for the taking too: leaves of honey locust, American sweetgum, red maple, Ohio Buckeye, pin oak, and of American elm — the tree that a century ago had complete sway over species in the Yard. Harvard poet Jorie Graham once wrote that — yes — fallen leaves possess a “jubilation of manyness.”